Zero to Singularity

Articulating the implicit theology of “Zero to One”

In the year 2023, after three centuries of rapid technological progress, one might reasonably expect humanity to have designed some mechanistic solution to reliably produce scientific discoveries and technological progress. Zero to One reveals that even in modernity, the act of creating new technology is deeply strange, and perhaps surprisingly, shares many features we normally associate with religious traditions. In its pages, we find ourselves reading about cults, mafias, secrets, conspiracies, grand designs, and founder-kings.

Upon closer inspection, Zero to One appears to be making even bolder claims. Technology startups don’t borrow from religion in a merely tactical or strategic sense. The act of technology creation is itself a miraculous quasi-theological product. Like the mystery of the creation of the universe, the creation of human technology is intrinsically positive-sum, and thus stands in stark contrast to the conservative, mean-reverting, zero-sum processes we see nearly everywhere else in the universe.

When we consider the Christian tenet that human life is distinguished by its intrinsic divinity, and subsequently consider the project of advancing human prosperity to be one of theological importance, the act of technology creation takes on an even more distinct Christian moral and ethical character. The whole of Zero to One is thus revealed to reflect a deeply Christian agenda– not only in it’s framing of modernity’s problems (technological stagnation), and in its prescription of potential solutions (definite optimism), but in its offering to the questions that lie at the very heart of humanity– questions of our faith, of the importance of human agency, and of the very meaning of our lives.

In a sense, Peter is merely stepping back and carefully taking score in Zero to One, revealing our world to be much, much stranger than any of us recognize. In so doing, he greatly widens the aperture through which we readily understand our universe, and the centrality of human life. Above all, Peter shows us that even in modernity, the consequences of our decisions are of grave importance. For the range of possible outcomes for humanity is very real and truly wide– from the apocalypse to the peace of the kingdom of God.

The miracle of technology

Let’s start with a simple question: what is the fundamental character of humanity? Zero to One offers two answers. The first answer is religious and it begins with the book of Genesis:

In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. - Genesis 1

God’s fundamental character is one of creation. It is his first and most important act in the Bible, and the act upon which everything else rests. In the beginning, he creates something out of nothing– the universe ex nihilo. Peter calls back to the universe’s miraculous beginnings in Zero to One’s very title, and in the book’s opening lines:

Every moment in business happens only once… The act of creation is singular, as is the moment of creation, and the result is something fresh and strange. - Zero to One

This idea of divine creation is critical to Peter's conception of humans. Humans were made in the image of God and we are differentiated from all other creatures of the earth by our ability to work miracles:

Humans are distinguished from other species by our ability to work miracles. We call these miracles technology.

What makes technology miraculous? Human technology contains the same miraculous character present in the very founding of the world because it allows us to create abundance ex nihilo:

Technology is miraculous because it allows us to do more with less… by creating new technologies, we rewrite the plan of the world.

Other animals are instinctively driven to build things like dams or honeycombs, but we are the only ones that can invent new things and better ways of making them.

This is Zero to One’s first insight: the creation of human technology properly understood is a miraculous act that has nearly no match and is consistent with the miracle of the creation of the universe. And by technology we, of course, don’t just mean software:

Properly understood, any new and better way of doing things is technology.

Technologies as old as irrigation, as new as penicillin, and as abstract as Western liberalism are all wealth generating because they promote human well-being in a way that is not strictly zero-sum. The miraculous character of technology creation is even more apparent when compared to nearly all other processes occurring in the universe which are fundamentally conservative. Whether it be conservation of energy or natural selection, there are very few examples of anything that can be called positive-sum creation happening in the natural world.

The necessary but zero-sum nature of mimesis

The second answer is biological. Humans are also risen apes from the animal kingdom. In this respect, we are the products of history, our environment, and of Darwinism. To be more precise, humanity’s fundamental character is mimetic, whereby we copy those that came before us, and those around us. This conception of humanity of course comes from Rene Girard’s mimetic theory, which is widely known to have been a big influence on Peter.

According to Girard, all cultural institutions, beginning with the acquisition of language by children from their parents, require this sort of mimetic activity, and so it is not overly reductionist to describe human brains as gigantic imitation machines. Because humanity would not exist without imitation, one cannot say that there is something wrong with imitation per se or that those humans who imitate others are somehow inferior to those humans who do not. The latter group, according to Girard, simply does not exist. – The Straussian Moment

Mimesis is how we acquire language, learn to collaborate, and form societies. It is arguably not even a flawed state in humanity, but a quality intrinsic to life itself. Its character is present in how DNA is replicated, how cells divide, and how animals reproduce. As humans copy each other's behaviors, hopes, fears and desires, we inevitably end up in a state of competition:

Competition is not just an economic concept or a simple inconvenience that individuals and companies must deal with in the marketplace. More than anything else, competition is an ideology– the ideology– that pervades our society and distorts our thinking.

It’s easy to see how competition arising from unrestrained mimesis leads to devastating Malthusian outcomes. Just turn on Animal Planet or look up “carrying capacity” in any high school biology textbook. Every other creature on earth can only be driven by mimetic instinct and is virtually undifferentiated from its peers, with the exception of some minuscule genetic variation. Without the God given capability of individual agency, animals can only act out their historic, genetic, pre-programmed behaviors in response to their environment, and can only be guided by the ruthlessness of Darwinism to change.

Humans aren’t entirely free of these brutal competitions. In the modern business context this manifests in the misguided economic ideal of “perfect competition”, whose description could describe Darwinism perfectly:

“Perfect competition” is considered both the ideal and the default state in Economics 101. So- called perfectly competitive markets achieve equilibrium when producer supply meets consumer demand. Every firm in a competitive market is undifferentiated and sells the same homogeneous products. Since no firm has any market power, they must all sell at whatever price the market determines. If there is money to be made, new firms will enter the market, increase supply, drive prices down, and thereby eliminate the profits that attracted them in the first place. If too many firms enter the market, they’ll suffer losses, some will fold, and prices will rise back to sustainable levels. Under perfect competition, in the long run no company makes an economic profit.

As competition increases, it destroys economic surpluses for its participants. In highly competitive markets with little capacity for differentiation the competition becomes more explicitly zero-sum, and humans must become increasingly ruthless to survive.

The problem with a competitive business goes beyond lack of profits. Imagine you’re running one of those restaurants in Mountain View. You’re not that different from dozens of your competitors, so you’ve got to fight hard to survive. If you offer affordable food with low margins, you can probably pay employees only minimum wage. And you’ll need to squeeze out every efficiency: that’s why small restaurants put Grandma to work at the register and make the kids wash dishes in the back. The competitive ecosystem pushes people toward ruthlessness or death.

Unrestrained competition and Darwinism may be “natural”, but its mechanisms are inhumane. Change in the natural world can only be guided by starvation, predation, violence and suffering. In this way, Darwinism is fundamentally incompatible with the most basic Christian notion of the inherent sanctity of human life, and Christian common sense demands that we strongly resist its application to humanity.

The Thielian conception of humanity

So, humans are fundamentally capable of positive-sum creation in the tradition of the biblical god, but humans are also fundamentally mimetic in the tradition of biological life. Here’s Zero to One’s second insight: each character can be modeled as a component of human progress– going from 0 to 1 (creation), and going from 1 to n (mimesis). Their productive combination represents humanity’s highest capacity for good and the swiftest path for the advancement of human well-being.

This is arguably Peter's most important contribution in Zero to One and his answer to the dilemmas raised a decade earlier in The Straussian Moment. Peter manages to combine “the gradualism of Darwinian evolution with the essentialism of the pre-Darwinians, stressing both the continuity and discontinuity of humanity with the rest of the natural order.” He merges a Girardian understanding of human behavior and mimesis, fundamentally rooted in biology, with a Judeo-Christian understanding of technology, fundamentally rooted in miraculous creation ex nihilo, producing a model of humanity that is both supernatural and pragmatic.

In fact of writing a book about creating startups Peter adds a critical element missing in Girard’s work: a popular, far reaching, and practical application of Girard’s ideas to the larger and more literal theological project of promoting peace and human flourishing.

We have some indication as to the correctness of Peter's model in the decisiveness of its explanatory powers over the biggest questions of human progress, and by the charisma with which it prescribes solutions. How do the free market and Western liberalism deliver progress? How can we understand the quality of progress in 2023? And what solutions can be prescribed to fix our technological stagnation?

Demystifying the free market

The free market is widely credited as having lifted the West out of poverty and is arguably the biggest driver of progress in human history. Casual observers conflate capitalism and competition and imagine them as the underlying mechanisms through which the free market delivers progress, but Peter famously points out that these concepts are actually antonyms:

Americans mythologize competition and credit it with saving us from socialist bread lines. Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away.

In Peter's model competition alone cannot be responsible for creating economic surpluses because competition alone is zero-sum and destroys surpluses. What then accounts for the free market’s ability to generate surpluses? Somewhat unintuitively, it is the free market’s accommodation of monopolies:

The world we live in is dynamic: it’s possible to invent new and better things. Creative monopolists give customers more choices by adding entirely new categories of abundance to the world. Creative monopolies aren’t just good for the rest of society; they’re powerful engines for making it better.

In other words, the origin of economic surpluses in the free market are neither from competition nor capitalism per se. In Peter's model, the divine creation of human technology ex nihilo is the only possible origin of economic surpluses in the free market. Deirdre McCloskey encapsulates this idea well when she describes “Innovism”, or the ability to incentivize innovation as the free market’s most essential good. In this framework, Western liberalism is also overtly compatible with the value generating character of the free market, insofar that it promotes liberty for more individuals to innovate and create new surpluses in the economy.

Competition is in a sense critical to a well functioning free market in two aspects. “Free entry” into the free market is a kind of competition when placed in the ultimate all-encompassing market which accommodates all human desires, but it is equally a misnomer because it is not obvious that the number of individual market categories that can be created through innovation has an upper limit. Competition’s underlying component, mimesis, is also an important multiplier to progress. Globalization or copying technologies into new markets is arguably the lowest cost way to rapidly improve the well-being of the greatest number of humans, but it alone is an incomplete solution and cannot be done indefinitely.

The permission of capital accumulation is also a necessary but insufficient premise for a well functioning free market, and certainly not a mechanism which can deliver progress in and of itself. Capitalism is necessary because the possibility of capturing monopoly profits strongly incentivizes the creation of new technologies.

Monopolies drive progress because the promise of years or even decades of monopoly profits provides a powerful incentive to innovate.

Thus, Peter’s model of human progress clarifies the value generating mechanics of the free market, and allows us to recognize the extent to which vertical, technological progress has stalled in the modern era.

The rise of our indefinite, pessimistic world

Since horizontal progress is necessarily zero-sum and distributive, it relies on the economic surpluses created from vertical, technological progress to function well. Correspondingly, its health is measured by the optimistic - pessimistic dichotomy. When a society has large surpluses, the economic pie feels like it’s growing, and the future feels optimistic. The world will be characterized by more abundance, and there will be more than enough to go around for everyone. When a society has fewer surpluses, the world feels like a pessimistic, ever darker place. The economic pie is no longer growing, and to get what you want, you will have to take it from someone else.

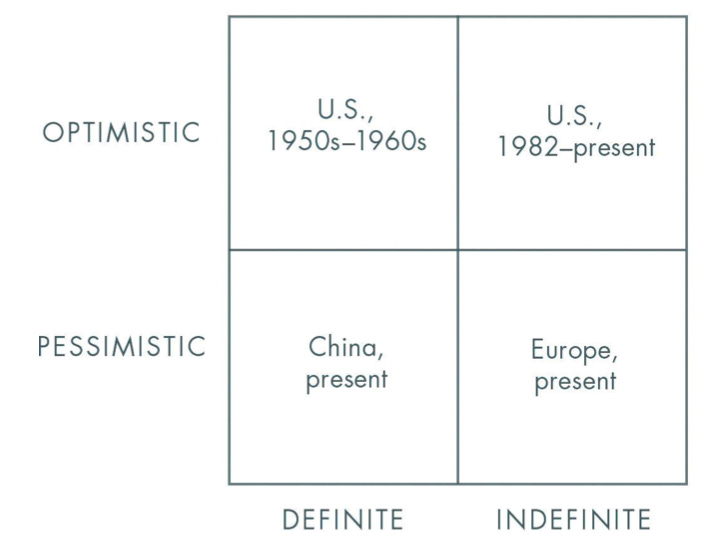

Vertical progress is the origin of economic surpluses, and is dependent on a society’s ability to incentivize the creation of new technologies. This places the contingency of technological progress on a different set of questions, captured by the definite - indefinite dichotomy. Are human individuals capable of changing the world for the better? Is the future definite and subject to some degree of personal design and independent discovery? Or are humans weak and inconsequential against the larger underlying forces which truly guide human history? Is the future infinite and ultimately unknowable, ruled by randomness?

Plotting the two categories in a matrix, you get the following categories which can describe all eras of human progress:

At the time of Zero to One’s publishing, Americans were arguably in an indefinite, optimistic mood. Americans had good reason to be optimistic– coming off the heels of three centuries of relentless technological progress, the West had created massive economic surpluses and Americans “inherited a richer society than any previous generation would have been able to imagine.”

Yet American society has also come to be nearly defined by its indefinite attitudes– its character is present in our schooling, in our science research, and in our political philosophy. We perhaps see it’s most overt manifestation in the primacy of banking, law, and finance in the modern era:

Instead of working for years to build a new product, indefinite optimists rearrange already- invented ones. Bankers make money by rearranging the capital structures of already existing companies. Lawyers resolve disputes over old things or help other people structure their affairs. And private equity investors and management consultants don’t start new businesses; they squeeze extra efficiency from old ones with incessant procedural optimizations.

Most Americans are no longer interested in making definite plans for the future in part because it has been a suboptimal strategy for so long. Why invest in the hard work of doing new things, when you can build a successful career by simply copying others? In a society with large existing economic surpluses, focusing on horizontal progress is a cheap and effective strategy.

Indefinite attitudes, and their expression in globalization, also appear extremely credible. Globalization is perhaps best epitomized in the nation of China, famous for its relentless copying and its disregard for intellectual property, but also for growing its economy by 8% year over year and having raised the greatest number of people out of poverty in human history.

But, as Peter’s model reveals, globalization and technology creation are actually two distinct, orthogonal forms of progress. One of our great errors in modernity is mistaking the health of globalization for the health of human progress more broadly. We naively believe that the same mechanisms which arguably make globalization successful– consensus, process, collaboration, and deliberation– are capable of generating technological progress all on their own.

In truth, such politics will never be a workable solution. Forget about the West, if China and India industrialize with today’s technologies, the environmental consequences will be catastrophic.

Without technological change, if China doubles its energy production over the next two decades, it will also double its air pollution. If every one of India’s hundreds of millions of households were to live the way Americans already do—using only today’s tools—the result would be environmentally catastrophic. Spreading old ways to create wealth around the world will result in devastation, not riches. In a world of scarce resources, globalization without new technology is unsustainable.

The unworkability of these policies is even more apparent today. Since 2014, America has arguably moved on to a more indefinite, pessimistic view of the world. It has been so long since meaningful technological progress has been made, and economic surpluses realized, that Americans rightly sense that the world is becoming more zero-sum. Without the engine of “Innovism” driving more surpluses, society turns inward and becomes fixated on questions of equality, fairness, and ultimately, of personal survival.

In this context, modern Western society’s obsession with diversity, representation, and reparations is only sensible. Politicians on the right and left are not interested in growing the economic pie because they don’t believe it is truly possible or that, if it is possible, that it will make a meaningful difference. Instead, they’ve become fixated on zero-sum questions of how to fairly divide whatever’s left.

The problem of America’s demythologized present

At the core of modern America’s indefinite attitudes is a deep seated belief in the weakness of the human individual. We have become extremely skeptical of the power of individuals to affect change, and ultimately believe that the life of any human is replaceable and of little consequence to the world.

In an era nearly defined by its globalization, this conclusion only makes sense. On the world stage, we rarely see individual scientists, engineers, or artists moving world affairs forward. Our most important initiatives are run by faceless organizations and their processes– the WTO, the IMF, the UN, the WHO, and the World Bank.

That these organizations have evolved to be structured this way is also merely sensible. The length of a productive human lifetime is relatively short, but companies and government agencies can last centuries. Any government agency that relies critically on individual human beings’ decision making to function will be fragile, because those individuals’ decision-making represent single points of failure. In startup culture this kind of vulnerability is called “bus factor”.

So instead these organizations develop processes to get things done, because processes obviate the need for critical thinking and human agency. Schools likewise prepare us to enter such a world from a young age. We are taught that executing processes is how success is achieved.

From an early age, we are taught that the right way to do things is to proceed one very small step at a time, day by day, grade by grade. If you overachieve and end up learning something that’s not on the test, you won’t receive credit for it. But in exchange for doing exactly what’s asked of you (and for doing it just a bit better than your peers), you’ll get an A.

The downstream consequence is that we treat individuals as disposable, replaceable parts in the infinite machinery of humanity. One of the most insidious and persuasive conclusions from this ideology is the consequence of statistics and the law of large numbers:

As globalization advances, people perceive the world as one homogeneous, highly competitive marketplace: the world is “flat.” Given that assumption, anyone who might have had the ambition to look for a secret will first ask himself: if it were possible to discover something new, wouldn’t someone from the faceless global talent pool of smarter and more creative people have found it already? This voice of doubt can dissuade people from even starting to look for secrets in a world that seems too big a place for any individual to contribute something unique.

Likewise, society reflects and reinforces this attitude from the outside. In the 21st century, Americans regard anyone with a grand plan for the future with suspicion. We don’t believe in big ideas, and don’t believe that an individual can discover something new and true contrary to the accepted wisdom, except in rare circumstances determined more by chance than by careful design. This is epitomized in Malcom Gladwell’s book Outliers which “declares… that success results from a ‘patchwork of lucky breaks and arbitrary advantages.”

But, Peter reminds us that we Americans were not always this way. Surveying old videos of Walt Disney’s EPCOT, or John F. Kennedy’s speech at Rice University, one is struck by how common ambitious and definite attitudes were back then. In the 1940s a school teacher named John Reber created a grand plan to dam the San Francisco Bay Area, producing massive reservoirs of freshwater and reclaiming thousands of acres of farm land. The plan was popular, and the Army Corps of Engineers eventually created a 1.5 acre model to simulate it. Reber’s plan ultimately failed, but the seriousness with which it was taken is indicative of that society’s willingness to believe in big ideas:

In the 1950s, people welcomed big plans and asked whether they would work. Today a grand plan coming from a schoolteacher would be dismissed as crankery, and a long-range vision coming from anyone more powerful would be derided as hubris. You can still visit the Bay Model in that Sausalito warehouse, but today it’s just a tourist attraction: big plans for the future have become archaic curiosities.

The positive framing of this change is that people today are much less likely to believe in cults.

Forty years ago, people were more open to the idea that not all knowledge was widely known. From the Communist Party to the Hare Krishnas, large numbers of people thought they could join some enlightened vanguard that would show them the Way. Very few people take unorthodox ideas seriously today, and the mainstream sees that as a sign of progress.

We can be glad that there are fewer crazy cults now, yet that gain has come at great cost: we have given up our sense of wonder at secrets left to be discovered.

It is at our peril that we mistake the disenchantment brought on by runaway globalization for mere wisdom. Yet, taking the contrary position today feels like a nearly impossible proposition. In such a large world, what hope is there for any individual person to make a difference?

The practical case for definite optimism

An indefinite pessimist might say we don’t see technological progress because people’s abilities are limited, and humanity’s remaining problems are hard. This mood effectively captures the philosophy of Ted Kaczynski, aka the Unabomber:

Kaczynski argued that modern people are depressed because all the world’s hard problems have already been solved. What’s left to do is either easy or impossible, and pursuing those tasks is deeply unsatisfying. What you can do, even a child can do; what you can’t do, even Einstein couldn’t have done.

But can it really be that humans have already solved all our hard problems? Here, Peter offers three observations of contradictory behavior which tell us that this cannot be true.

The seemingly all-powerful systems which globalization has produced, and which quietly tell us in the law of large numbers that the individual has little hope of contributing anything unique to society, have gaping structural inefficiencies. This is revealed in the exuberant bubbles that pervade our markets.

…the existence of financial bubbles shows that markets can have extraordinary inefficiencies. (And the more people believe in efficiency, the bigger the bubbles get.) In 2005 Fed chairman Alan Greenspan had to acknowledge some “signs of froth in local markets” but stated that “a bubble in home prices for the nation as a whole does not appear likely.” The market reflected all knowable information and couldn’t be questioned. Then home prices fell across the country, and the financial crisis of 2008 wiped out trillions. The future turned out to hold many secrets that economists could not make vanish simply by ignoring them.

If globalization could produce a system that accurately captured and reflected all knowledge, including that of human potential, one would expect there to be no such bubbles. The size, pervasiveness, and damage of these bubbles reveal the degree to which the organization of human society is still structurally inadequate.

But just because large inefficiencies exist doesn’t mean that people are necessarily capable of solving them. Such inefficiencies may be so hidden, or their dysfunctions so deeply embedded into human society, that no individual is capable of changing them.

The existence of open secrets upon which Silicon Valley’s most successful companies of the last decade have been built seems to contradict this. Airbnb, Uber, and Facebook have built massively valuable companies on secrets hiding in plain view:

Consider the Silicon Valley startups that have harnessed the spare capacity that is all around us but often ignored… Airbnb saw untapped supply and unaddressed demand where others saw nothing at all. The same is true of private car services Lyft and Uber. Few people imagined that it was possible to build a billion-dollar business by simply connecting people who want to go places with people willing to drive them there.

That some of humanity’s most valuable companies can be built on what in retrospect appear to be simple insights is a powerful argument for the existence of more open secrets yet to be found.

The same reason that so many internet companies, including Facebook, are often underestimated— their very simplicity—is itself an argument for secrets. If insights that look so elementary in retrospect can support important and valuable businesses, there must remain many great companies still to start.

The final and arguably most powerful argument for definite optimism is the existence and ubiquity of power laws. In everyday life, the presence of power laws is rarely recognized. It is only upon closer inspection that we realize they govern almost everything we do.

In 1906, economist Vilfredo Pareto discovered what became the “Pareto principle”... This extraordinarily stark pattern, in which a small few radically outstrip all rivals, surrounds us everywhere in the natural and social world. The most destructive earthquakes are many times more powerful than all smaller earthquakes combined. The biggest cities dwarf all mere towns put together. And monopoly businesses capture more value than millions of undifferentiated competitors…. the power law—so named because exponential equations describe severely unequal distributions—is the law of the universe. It defines our surroundings so completely that we usually don’t even see it.

Power laws, open secrets, and large revealed inefficiencies in society’s existing structure tell us that powerful levers for progress exist all around us. According to Peter, the real reason we haven’t seen technological progress in the last 40 years is because we have simply stopped seriously looking. The indefinite attitudes that pervade our society are powerful self-fulfilling prophecies for never discovering or creating anything radically new and important (i.e. creating technology). And we can only uncover powerful secrets and create radically better technology if we force ourselves to look.

If you treat the future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it. But if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up on trying to master it.

The actual truth is that there are many more secrets left to find, but they will yield only to relentless searchers. There is more to do in science, medicine, engineering, and in technology of all kinds. But we will never learn any of these secrets unless we demand to know them and force ourselves to look.

Thus, Peter lays the question of technological progress at the feet of our culture– our ideology, our rhetoric, our ethics, and our values. At its highest level, the task of restarting human technological progress returns us to the theological questions of humanity’s purpose, individual belief, and ultimately, of faith. It is here that Peter’s conception of humanity presents its final and most incisive challenge against the inevitability of modernity’s technological stagnation.

The return of intelligent design

Recall the opening lines of Zero to One and the Book of Genesis. The great question of creation in our world is still a deep mystery, and one that we would do well to reflect on. By analogy, if the simple, mechanistic descriptions of Newtonian physics can accurately describe 99% of our daily reality, it’s worth remembering that it is also fundamentally incomplete, because our universe also contains black holes and began with the Big Bang.

Darwin’s theory explains the origin of trilobites and dinosaurs, but can it be extended to domains that are far removed? Just as Newtonian physics can’t explain black holes or the Big Bang, it’s not clear that Darwinian biology should explain how to build a better society or how to create a new business out of nothing.

By that same token, the regular, mechanistic, and statistical powers that seemingly control us provide an incomplete picture of human life. In any given moment, their size and consistency may feel infinite and absolute, but careful inspection shows them to be fundamentally incomplete and thus reveal our world to be far stranger than we know. For Peter, there is a very real and literal divinity intrinsic to human life, and we see evidence of its miraculous presence everywhere around us– if only we know where and how to look.

For one, neither reason nor faith alone appear capable of sustaining the weight of humanity’s creative and destructive potential. Reason teaches us how the world works, about deduction, and about cause and effect, but it also teaches us that we are small, common, and inconsequential. It is predisposed to nihilism, which eventually regards human life with disdain, and is easily led astray, as in the violence and madness of the 20th century’s most secular societies.

Faith is the source of our inspiration and creation, and it quietly tells us that human souls are sacred and intrinsically worthy. But our eager willingness to believe in the power of faith– of any faith– is all too capable of producing its own pathologies, as in the blind faith of suicidal cults or reclusive monastic asceticism.

Zero to One shows us that reason and faith aren’t merely compatible– their combination may be essential to humanity. Human life itself is perhaps a first order expression of this underlying unity. As descendants of apes, we share in life’s humble material origins, but humanity’s capacity for inspired creation equally distinguishes it from all other life which can only live and die by its zero-sum Darwinian competitions.

And it is here, between reason and faith, that we find the central project of human progress, which itself has an equally distinct material-theological character. Human progress’s material products are economic growth and the reduction of conflict from zero-sum competitions; its theological products— the veneration and protection of sacred human lives and humanity’s biblical fulfillment as faithful stewards of God’s creations.

Above all, we can judge Peter’s conception of an industrious Christian life by the fruits that they bear: by the charisma with which it instructs us to live with purpose and urgency, in its framing of our lives as an arena for the hard but potentially redemptive work of human creation, and by the answer it gives to the call deep inside each of us, that our lives are of consequence, that we have been put on this planet for a reason, and that the things we do truly matter.

The mythical founder-king of Silicon Valley himself knew this well:

You can't connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.

You have to trust in something -- your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever. This approach has never let me down, and it has made all the difference in my life. – Steve Jobs

In the end, Zero to One reveals to us what were once elementary truths just one hundred years ago– that humans are not animals, that the question of faith remains central to human life, and that the things we decide to do with our lives don’t just matter– in humanity’s final days, they may end up being the only things that matter.

This was very well written and insightful. I'm also reminded of Yuval Noah Harari's argument in Sapiens about how religion has played a crucial role in human development by providing a shared set of beliefs, values, and norms that allow people to cooperate and form complex societies.

Looking forward to the next one!